Note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander readers are respectfully advised that this page contains images of places and deceased persons which could cause sorrow. All archival photographs are reproduced with cultural permission.

The 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry marked the only occasion in the history of nineteenth-century Victoria when an official commission was appointed to address Aboriginal peoples' calls for land and self-determination, and one of the few times that Aboriginal witnesses were called to give evidence on matters concerning their own lives and interests. As such, it is a rare and historically significant moment in the history of relations between Victoria's indigenous and settler populations, in which Aboriginal peoples’ claims to justice were addressed by the colonial government in an official forum. For the Kulin clans living at Coranderrk, the stakes could not have been any higher; this was the last chance to contest an eviction that would have completed their total dispossession.

The 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry

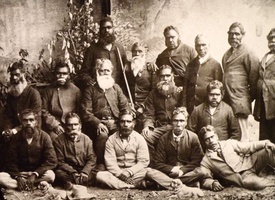

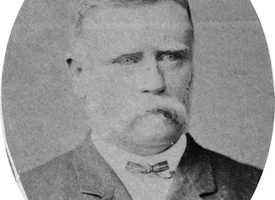

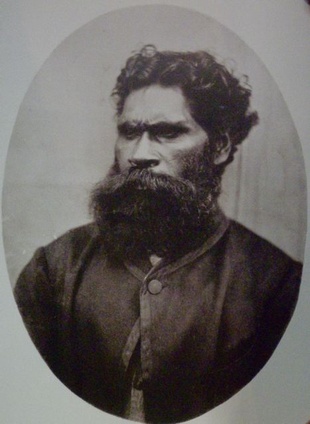

In response to the threat of being dispossessed of their lands yet again, the men and women of Coranderrk embarked on a sophisticated and sustained campaign to impede the break-up of the station and bring about the reinstatement of their ally, John Green. Under the leadership of the charismatic Ngurungaeta (clan head) of the Wurundjeri people, William Barak, the Coranderrk community made their voices loud and clear, writing petitions and letters to ministers, and forming deputations by walking into Melbourne to voice their protests directly to the Premier. Spanning several years, the Coranderrk protest turned into one of the earliest sustained Aboriginal land-rights and self-determination movements.

In response to the threat of being dispossessed of their lands yet again, the men and women of Coranderrk embarked on a sophisticated and sustained campaign to impede the break-up of the station and bring about the reinstatement of their ally, John Green. Under the leadership of the charismatic Ngurungaeta (clan head) of the Wurundjeri people, William Barak, the Coranderrk community made their voices loud and clear, writing petitions and letters to ministers, and forming deputations by walking into Melbourne to voice their protests directly to the Premier. Spanning several years, the Coranderrk protest turned into one of the earliest sustained Aboriginal land-rights and self-determination movements.

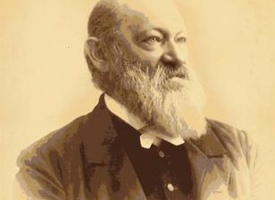

Thanks to the determination of the men and women of Coranderrk, and to the support of influential allies in the white settler community who lent weight to their cause – such as the feisty Anne Fraser Bon – the campaign became so effective that Government officials could no longer ignore it. In 1881, Chief-Secretary Graham Berry appointed a Parliamentary Inquiry to investigate the Board’s management of Coranderrk and to decide upon its future. The testimony from this Inquiry gives us an insight into the practices of structural discrimination today.

The 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry, officially titled ‘The Board Appointed to Enquire into, and Report upon, the Present Condition and Management of the Coranderrk Station’, lasted two and a half months, from late September to early December 1881. Its nine commissioners, including eight prominent men and the redoubtable wealthy widow Anne Bon, held ten hearings, three of which were held at Coranderrk. They examined 69 witnesses, both Aboriginal and European and asked 5,349 questions. The Inquiry had significant influence: its findings had the potential to trigger a reform of colonial policies, not just towards the management of Coranderrk but all of Victoria's Aboriginal population. As such, the 1881 Coranderrk Inquiry attracted serious public and political interest.

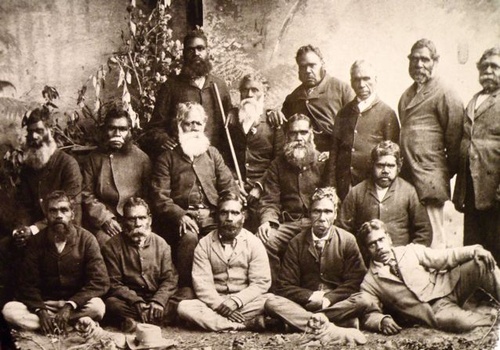

The Inquiry did not constitute a level playing field for the Coranderrk witnesses. Although their testimonies were consistent and often backed by carefully witnessed statements, the conservative Commissioners' prejudices tended to favour the statements of European witnesses over theirs – including those of the Board's own officials. But the Coranderrk residents did not let these disadvantages deter them from fully engaging with the Inquiry's mechanism of justice – as imperfect as it was. In order to persuade the Commissioners of their collective desire to remain on the station, eighteen men, four women and one young boy gave evidence. Despite the serious risks associated with contesting the Board's authority, many were outspoken witnesses and were not cowed by officialdom; they delivered their testimonies with patience, dignity and poise. The Coranderrk witnesses performed admirably, refuting their critics' insinuations that their protest had been fomented by 'outside influences' and that their complaints were simply motivated by a petty desire for extra rations and welfare. They defended the men's work-ethic, the women's morality, and supported their claims with written evidence. Most importantly, they presented a united front and chose their words carefully. Their fundamental demands were simple yet radical: as stated in their final petition – signed by Barak and forty-five men, women and children: "We want the Board and the Inspector, Captain Page, to be no longer over us. We want only one man here, and that is Mr. John Green, and the station to be under the Chief Secretary; then we will show the country that the station could self-support itself."

The Inquiry did not constitute a level playing field for the Coranderrk witnesses. Although their testimonies were consistent and often backed by carefully witnessed statements, the conservative Commissioners' prejudices tended to favour the statements of European witnesses over theirs – including those of the Board's own officials. But the Coranderrk residents did not let these disadvantages deter them from fully engaging with the Inquiry's mechanism of justice – as imperfect as it was. In order to persuade the Commissioners of their collective desire to remain on the station, eighteen men, four women and one young boy gave evidence. Despite the serious risks associated with contesting the Board's authority, many were outspoken witnesses and were not cowed by officialdom; they delivered their testimonies with patience, dignity and poise. The Coranderrk witnesses performed admirably, refuting their critics' insinuations that their protest had been fomented by 'outside influences' and that their complaints were simply motivated by a petty desire for extra rations and welfare. They defended the men's work-ethic, the women's morality, and supported their claims with written evidence. Most importantly, they presented a united front and chose their words carefully. Their fundamental demands were simple yet radical: as stated in their final petition – signed by Barak and forty-five men, women and children: "We want the Board and the Inspector, Captain Page, to be no longer over us. We want only one man here, and that is Mr. John Green, and the station to be under the Chief Secretary; then we will show the country that the station could self-support itself."

The 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry and its minutes of evidence, the documentary record of the Inquiry, allow us to consider how justice and injustice are addressed through government responses, in particular, to examine the relationship between justice and governance.

Key Figures in the Inquiry

Indigenous | Settler |

| Thomas Bamfield: clan head of the Taungerong, Coranderrk resident and a leading figure in the Coranderrk struggle | Anne Fraser Bon: one of the nine Commissioners on the Inquiry, and a wealthy widow and humanitarian who had a strong interest in the welfare of Victorian Aboriginal people |

| Alice Grant: a young Taungerong woman and Coranderrk resident who was assistant teacher and washerwoman | Ewen Cameron: Chairman of the Inquiry, and Member of Parliament for Evelyn, the electorate where Coranderrk was located |

| William Barak: Ngurungaeta (clan head) of the Woiwurrung clans and leader of the Coranderrk community | Rev. Strickland: an Anglican missionary who was the manager of Coranderrk at the time of the Inquiry |

| Robert Wandon: member of the Woiwurrung clans and a prominent member of the Coranderrk community, nephew of Barak | Henry Jennings: a lawyer and founding member of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines. |

| Thomas Dunolly: one of Barak’s spokespersons who wrote the Coranderrk residents’ letters and petitions | Christian Ogilvie: John Green’s successor as Inspector of Aborigines for the Board and a temporary manager at Coranderrk |

| Caroline Morgan: Dja Dja Wurrung woman, mother and Coranderrk resident | Rev. Hagenauer: an influential Moravian missionary and manager of the Ramahyuck mission in Gippsland, who testified in the Board’s defence |

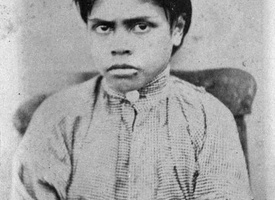

| Phinnimore Jackson: 13 year old orphan and Coranderrk resident | Edward Curr: a member of the Board, public servant and long time squatter who was experienced in managing pastoral stations |

| Alfred Davis: One of the young Coranderrk men who came to rescue Phinnimore Jackson after the latter was given a beating by Rev. Strickland | Eleanor McKie: Matron at the Melbourne Hospital where Aboriginal people were often treated |

| Captain Page: Secretary and Inspector of the Board at the time of the Inquiry | |

| Thomas Harris: A white labourer living and working at Coranderrk as farm overseer; he married Alice Grant shortly after the Inquiry | |

| Constable Michael Tevlin: police officer in Healesville and district, including Coranderrk | |

| George Syme: former member of the Board, journalist and editor of the regional newspaper the Leader | |

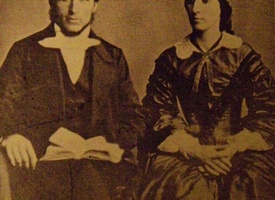

| John Green: founder and first manager of Coranderrk; former Inspector for the Board. |

A brief history Of Coranderrk

The history of Coranderrk provides a window onto the history of colonial dispossession in settler states. The Kulin nations were among the first in Victoria to experience the impact of settler-colonisation, as pastoralist entrepreneurs, squatters and convict workers took possession of lands around Port Phillip Bay, which the British Crown claimed as part of the colony of New South Wales in 1836. They brought herds of cattle and sheep, as well as firearms, alcohol and diseases, which wreaked destruction of genocidal proportions. At the heart of the conflict was land. For the Kulin, it was an essential and inseparable part of their identity, spirituality and way of life; to the newcomers, a key source of economic wealth, and the primary reason for their migration. Armed resistance against the invaders resulted in heavy Kulin casualties at the hands of the colonisers' superior military power. Without a fixed frontier to check settler expansion the same pattern of dispossession was repeated rapidly across Victoria, as many other Aboriginal nations were pushed to the very edge of survival, leading to the belief among Europeans that 'the natives' would soon simply die out.

From the 1840s in Victoria, a new phase of Aboriginal activism emerged. In 1859, Simon Wonga led a delegation of Kulin people to meet with government officials to request a grant of land to settle and farm in Acheron, in the hills beyond Melbourne. Coinciding with an 1859 Select Committee of the Legislative Assembly of Victoria that recommended the creation of reserves in Aboriginal home lands under the supervision of missionaries, the delegation was one of several attempts by Aboriginal leaders in Victoria to establish a permanent and productive stake in the land in sites of their choosing.

From the 1840s in Victoria, a new phase of Aboriginal activism emerged. In 1859, Simon Wonga led a delegation of Kulin people to meet with government officials to request a grant of land to settle and farm in Acheron, in the hills beyond Melbourne. Coinciding with an 1859 Select Committee of the Legislative Assembly of Victoria that recommended the creation of reserves in Aboriginal home lands under the supervision of missionaries, the delegation was one of several attempts by Aboriginal leaders in Victoria to establish a permanent and productive stake in the land in sites of their choosing.

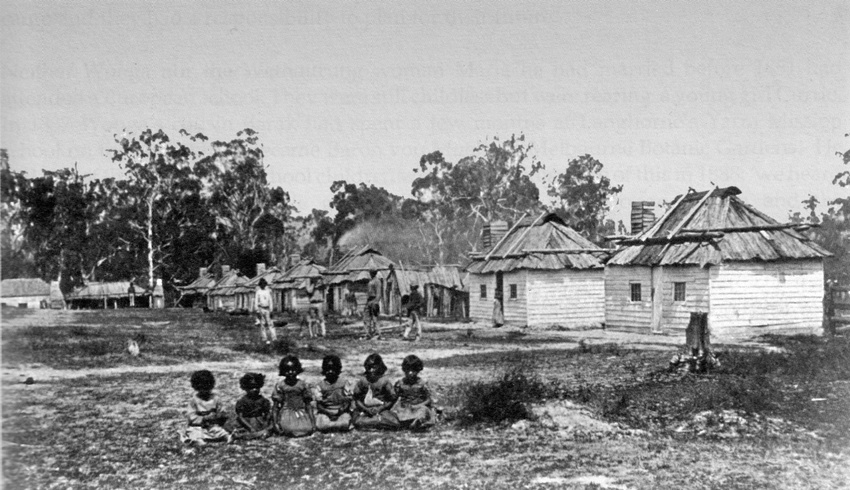

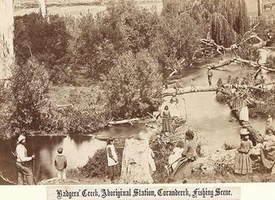

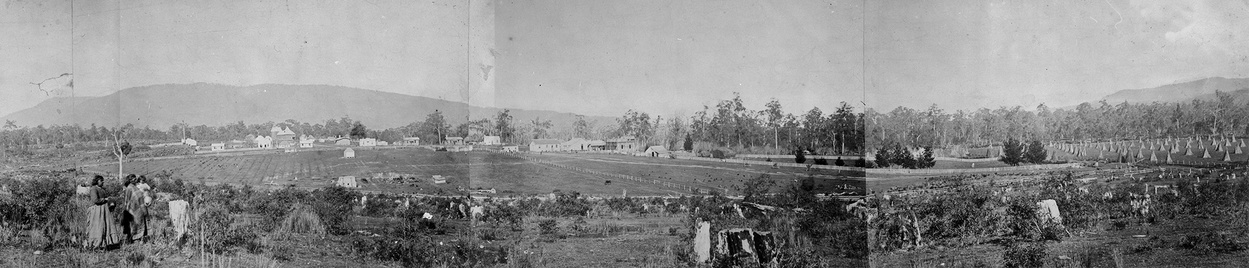

The Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve was established in 1863 and situated around 60km north-east of Melbourne outside the present-day town of Healesville. Under the leadership of Woiwurrung leaders Simon Wonga and William Barak – in collaboration with Scottish lay-preacher, John Green – the Kulin clans chose Coranderrk as a place where they agreed to settle down to farm the land, and live in peace. Within twelve years it was a home for 158 men, women and children. Coranderrk was one of six reserves that the government eventually established throughout the colony.

The Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve was established in 1863 and situated around 60km north-east of Melbourne outside the present-day town of Healesville. Under the leadership of Woiwurrung leaders Simon Wonga and William Barak – in collaboration with Scottish lay-preacher, John Green – the Kulin clans chose Coranderrk as a place where they agreed to settle down to farm the land, and live in peace. Within twelve years it was a home for 158 men, women and children. Coranderrk was one of six reserves that the government eventually established throughout the colony.

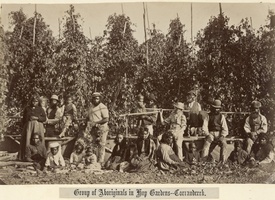

But as Coranderrk grew, so too did settler-colonial hunger for land. By the early 1870s, white farms virtually surrounded the reserve and the Aboriginal Protection Board – pressured by powerful lobbies with a vested interest in purchasing and settling the prime agricultural land of Coranderrk – began to consider ways of relocating the Aboriginal people. In 1874, for refusing to cooperate in this plan, John Green was dismissed by the Board as manager of Coranderrk.

The history of Coranderrk vividly illustrates the ways in which settler-colonisation impacted on Indigenous people in Victoria: from the decimation of the Aboriginal population through warfare and frontier violence, to the containment of the survivors on missions and reserves; and eventually, the implementation of government policies designed to disperse and absorb the remaining population into the settler community. The latter policies, enshrined in law as the 1886 'Half-Caste' Act, ultimately resulted in Coranderrk's demise by forcing its residents off the station whilst the land was gradually parcelled out to settlers.

The 1886 'Half-Caste Act'

In the years that followed the 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry, the Board lobbied vigorously to implement a new policy for governing the Aboriginal population of Victoria. The result was the ultimate destruction of Coranderrk as well as many other Aboriginal communities across the colony: including Framlingham, Lake Condah and Lake Tyers. With the passing of the so-called 1886 'Half-Caste Act', the Board could decree that: 'All able-bodied half-castes under the age of 35 years should be told to look out for employment, or seek settlement elsewhere.' Youths who had turned thirteen would be apprenticed out, and the girls placed into service with white families while 'neglected' children were to be transferred to white orphanages or industrial schools. Many of these youths were never to return to the stations or their families. As explained by the Board itself, the intention of this policy was to erase all traces of Aboriginal identity among the 'half-castes'.

The 'Half-Caste' Act was a heartless law. Not just at Coranderrk but across the colony, Aboriginal communities were broken up, separating family members from one another and from their Country. Some attempted to remain close to their former homes on the reserves; they clung to their traditional lands and their families by living in fringe camps or townships. Others sought to make a new life by moving to urban areas where, in order to cope, some found it necessary to deny their origins and to raise their children without telling them about their Aboriginal ancestry. In these and other ways, the 1886 'Half-Caste Act' caused a level of cultural and social devastation that would reverberate profoundly across future generations, as almost all Victorian Aboriginal people today are descended from the former residents of the reserves.

The Coranderrk residents had risked everything in order to fight for their land and self-determination. They had led a successful campaign to save their home, and waged it according to the colonisers' own rules and methods, using the written word and white political discourse. In the process of doing so, they made powerful allies and even more powerful enemies. Eventually, the Board prevailed; but it had to introduce a new Act of Parliament in order to do so.

Archival Photos

* Reproduced with cultural permissions from Coranderrk descendants and the Wurundjeri Land Council.

Visiting Coranderrk

Coranderrk is now a 200 acre property owned and managed by the Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation. It is a private property and a working farm so access is limited.

The property is open to the public for special events such as festivals and the annual walk to Coranderrk. Details of these events are posted on the Coranderrk Facebook page. Visits by school groups and community organisations can be arranged by appointment. Contact Brooke and Jacqui on coranderrkfestival@hotmail.

The cemetery is managed by the Wurundjeri Tribe Land Cultural Heritage Council. To discuss arrangements for visiting the cemetery, please contact Wurundjeri Land Council: Abbotsford Convent, St Heliers Street, Victoria, tel: (03) 9416 2905

My family history connection

If you are interested in finding out more about your Koorie family history, please contact the Koorie Heritage Trust:

Koorie Heritage Trust - Koorie Family History Service

Level 3 Yarra Building, Federation Square

Cnr Flinders and Swanston Streets

Melbourne VIC 3000

tel: (03) 866 6329

email: familyhistory@koorieheritagetrust.com.

All information that you provide will be treated in the strictest confidence.

Hear what Coranderrk descendants have to say

- Mission Voices: http://www.abc.net.au/missionvoices

- "Leave Us Here: 150 years of Coranderrk", 2013 ABC Radio interview with senior descendants of Coranderrk, including Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin, Murrundindi, Aunty Carolyn Briggs, Uncle Wayne Atkinson. Listen to the podcast here.